Prepare Illustrator File For Wcreent Print

Creating Clean Artwork and Design for Screen Printing. Preparing artwork for screen printing is different from any other type of design. Even professional graphic designers sometimes have trouble with it. So here’s a quick primer on how to create artwork that’s clean and screen-print-ready using Adobe Illustrator. Adobe Illustrator CC. First, convert all text to outlines. Select All. Type Create outline. File Save as. Set format to Adobe PDF. Start with the High Quality Print Adobe PDF preset. Make sure you settings match the screen shots that follow (img. B-D) The last four tabs can be left with default settings. Click Save PDF (img. Learn how to prepare an image for screen printing and other t-shirt design. If you are creating your file in Adobe Illustrator or another Vector-based.

- Prepare Illustrator File For Screen Printing

- Prepare Illustrator File For Wcreent Printers

- Prepare Illustrator File For Wcreent Printable

Printing Techniques

Preparing Your Artwork File

1. Create Layers for Each Color

2. Create a Temporary Background Color Layer

3. Remove Excess Objects From the Layer

4. Outline All Strokes

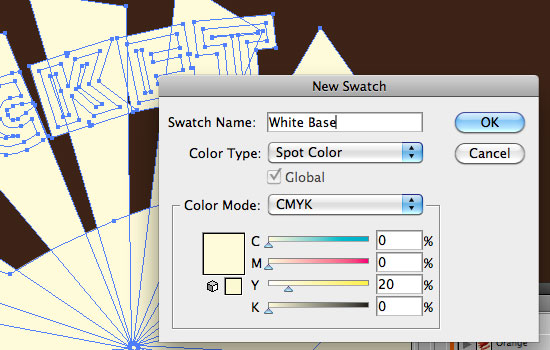

Object ? Path ? Outline Stroke. This ensures consistency if the artwork needs to be resized (Strokes can often be pushed out of proportion when resized with the Scale tool).5. Create and Apply a Custom Spot Color

Potential mis-registration of two colours, seen between orange and dark red

Object ? Path ? Offset Path. Offset the path by 1 mm to make the object larger in shape. Oftentimes printers specify how much Trap they require, similar to how they might specify Bleed. On this artwork, the white background outlines the color objects, but if you wanted the white to be printed directly behind the colors, without a white outline, you could offset the path of the White objects by a minus figure (for example-1mm).Left: Before offsetting path by 1mm. Right: After offsetting path to create Trap

7. Deciding on a Spot Color

Pantone Colors can be found under

Window ? Swatch Libraries ? Color Books8. Knocking Out for the Trap Below

Window ? Pathfinder) to Exclude the highlight color, effectively creating a void in the object shapes. This is Knockout; but as we created Trap on the Orange layer objects, we won’t get any registration issues. When using the Exclude tool, the object takes the color of the top object which is excluded. Change the color back to the original Dark Red using the Eyedropper tool on one of the other other objects.The Exclude tool (circled in green) is excellent for removing shapes from within objects

9. Trap is Not Always Necessary

For smaller text and objects, the Trap is too small, so the object is Overprinted instead

10. Checking Your Separations

Windows ? Separations Preview. From the window that opens, first check the Overprint Preview box and then hide the CMYK separations by clicking the eye icon beside CMYK. The temporary dark background should disappear.Separation of the three colors before Overprint is set

11. Setting Objects to Overprint

Window ? Attributes. With all the Orange objects selected, check the Overprint Fill box in the Attributes window. Do the same with the Dark Red layer, ensuring all the Dark Red objects are selected when you check the Overprint Fill box in the Attributes window.12. Recheck Your Separations

Left: Trap can be seen by darkened area around Orange. Right: White base returns to a solid shape (shown with temporary background, for illustrative purposes)

13. Ensure There are No CMYK Objects in the Artwork

File ? Print.Select your printer as Adobe Postscript File and click the Output option on the left side. Select Mode as Separations (Host-Based). On the list of colors below, if the printer icons shows next to any of the process colors (Process Cyan, Process Magenta, Process Yellow or Process Black), you have elements in your artwork which are set in CMYK colors.Checking for CMYK objects using the Print dialog box

14. Finish Up and Send It Off

Final Note

This post is about preparing InDesign documents to be printed. It’s a long and detailed post, and designed to be worked through (but not necessarily in one go). If you want to work though it as you read, sign up below to access the free 60 page downloadable pdf:

You’ll need a CC version of InDesign to work through the exercises - if you don’t have it, you can download a 30 day free trial version from adobe.com.

You’ll work through a series of documents, each of which will help demonstrate some different things to be aware of when you’re sending a document to be printed. Here’s an outline of what you’ll learn:

An overview of the 'preflight' process

How to check for missing images

How to check images that have been modified

What CMYK colour is

How to check if images are CMYK

What image resolution is

How to check the resolution of images

What bleeds are

How to check if bleeds are used and how to set them up

How to check for missing fonts

How to create a print ready pdf

An overview of the preflight process

The first document you’ll prepare for print has essentially no problems with it, but you’ll work through it to get used to some of the different concepts, terminology and areas of InDesign that you’ll need to become familiar with.

From the File menu choose Open to open the a 1-Introduction document. This advert is deliberately straightforward and will cause no problems when it’s sent to print*, so you’ll use it largely to compare with the documents that will present problems. All you’re going to do here is take a close look at the images used within it, then create a pdf that’s ready to send to a printer.

* As you work through these documents you’re going to learn how to check these possible areas of concern before sending a document to a printer: bleed,swatches,fonts, images and transparency. This first document does not require bleed, it uses only the default black swatch, it uses fonts that come installed with InDesign and it features no transparency.

Open the Links Panel by clicking on it at the top right of your screen.

The Links Panel contains list of all the images that have been imported into the document (using the File>Place command). When you place an image into InDesign it is not strictly imported into the document; instead a lower quality version of it is brought in which is linked to the original file on your computer. It’s important that these links are maintained, so that when you either create a pdf or a package to send to a printer (more about these later) InDesign can retrieve the full quality image from the original file.

If InDesign is not able to locate the original file because it’s been moved or renamed, you’ll see a red question mark next to the image in the Links Panel’s status column (underneath the triangular icon with the exclamation mark). In the case of these images the column should be empty because they are properly linked.

The other preliminary thing to check with the links is to make sure that they haven’t been modified since they were placed into InDesign. Later on you’ll learn how to modify images in a way that ensures InDesign can keep track of them, but for now, all you need to know is that if an image has been modified without InDesign knowing, there will be a yellow exclamation mark icon in the status column next to it. As before, this should not be the case for these images.

About CMYK

The majority of all commercially printed work is printed using Four Colour Process (alternatively called Four Colour, CMYK, Full Colour, Process Colour). This works by printing the four process colours, Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and blacK (hence CMYK) in a close arrangement of tiny dots in combinations that can simulate millions of different colours. If you look on the spine of a newspaper you’ll probably see the letters CMYK, or possibly little squares or circles printed of those colours. As a general guide, anything you produce that has a colour photograph on it will be produced in Four Colour Process.

If you are creating a document which will be printed in Process Colour, any image you place into InDesign should ideally be defined using CMYK*. This means that every one of the thousands or millions of pixels** that make up the image contains four pieces of information: how much Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and blacK. As digital cameras and most scanners work in RGB (like monitors, they work with light rather than ink), the majority of the images you will come across will probably be made up of RGB pixels.

* I say ideally because even if the images are not in CMYK, it’s possible for InDesign to convert them when creating a pdf, as you’ll discover later.

** You’re probably familiar with the term pixels – if not, it means the tiny squares of colour that make up a digital image. That is essentially all a digital photograph is – many thousands of tiny squares, each one capable of having its own unique colour or shade.

To see more information about the 1.jpg image, click on its name in the Links Panel.

Information about the image appears in the Link Info section at the bottom of the panel.

As you should be able to see from the screenshot above, the Colour Space of this image is CMYK. Click on all of the other jpg images in turn to check that they all are too. The final image listed (with the .ai suffix) is an Illustrator file. Leave this for now, but later you’ll explore a specific issue that can arise with this type of image.

About resolution

As well as checking images to ensure that they are not missing, not modified and have a CMYK colour space, you will also need to check their Resolution. Resolution essentially determines whether an image is of suitable quality to print. It is measured in ppi, the number of pixels per inch. For an image to be suitable quality for on screen work, it needs to have around 72ppi. But for printed work, a resolution of around 300ppi is advised. Printers often talk of dpi, rather than ppi, but it refers to the same thing. They also will refer to “High res” and “Low res” images, meaning high and low resolution, again high res normally meaning around 300ppi.

The Link Info for the 1.jpg image is shown above. Its resolution is shown as Actual ppi and Effective ppi. The Actual ppi is resolution of the image at its original size (300) and the Effective ppi is the resolution at the sized that it’s used on the page (312)*.

* The reason they are different is because the image has been made slightly smaller within InDesign, and as it’s measured by the number of pixels per inch of the image, if the image is made smaller the resolution will consequently go up. This is what is meant by the Effective ppi.

Click on each link in turn and you should see that for each one the Effective ppi is around 300, which is what you should ideally be aiming for. If they are not, you’ll be taking a risk that they will look poor quality.

Creating a print-ready pdf

As mentioned previously, whilst there are several other checks you’d normally make before sending your document to be printed, in this case you’ve made all the appropriate ones, so now you’ll export the advert as a pdf.

To create a pdf choose Export from the File menu. In the dialogue box that appears you’ll need to choose the Adobe PDF (Print) format, give it an appropriate name and save it in a suitable location. Once you’ve done that, a dialogue box appears that contains a choice of pdf export options. Whole books have been written on the best settings to use here – I’m going to simply suggest two options.

The first is to ask your printer to supply you with a Preset of the settings they would recommend. They can either talk the setting through to you for you to type in, or send you a job options file. For the purpose of this exercise you’ll continue to the next step, but the footnote below gives you instructions to follow if you are sent settings by your printer.

If they were to supply you with a file, you’d choose File>Adobe PDF presets>Define, then press the Load button, locate the file they’d sent, then press the Done button. When you next use the File>Export command, the options they sent will be in the list of Adobe PDF Presets at the top of the dialogue box.

In your case (and generally in the absence of advice or a preset given by your printer), choose the [PDF/X-1a:2001] preset from the options at the top of the Export Adobe PDF dialogue box. This preset’s settings were created to be used in advertising, and are generally agreed to work amongst print professionals, so you’re unlikely to get any nasty surprises. Press the Export button to finish creating the pdf, and if you want to look at it, locate it where you saved it and double-click on it to open it.

Summary of checks you made so far:

Checked for missing images (Links Panel: Status column)

Checked for modified images (Links Panel: Status column)

Checked that images were CMYK (Links Panel: Link Info)

Checked the resolution of images (Links Panel: Link Info)

Summary of commands used so far:

File>Open

File>Export (to create a pdf)

2. Essential checks: bleeds, fonts, links, resolution

The previous document was setup ready to go to print, but this one is not. Here you’ll discover how to work with images that are missing, images with a low resolution, fonts that are missing and learn about bleeds.

From the File menu choose Open to open the a 2-Essential-checks document. Before the document has even opened you should be presented with a dialogue box warning you that one of the links is missing.

Once you’ve pressed the OK button you’ll probably* be presented with another dialogue box, this time telling you that this document uses a font that you don’t have installed on your computer.

* If you’ve previously installed this font on your computer you won’t see this dialogue box appear.

The dialogue box invites you to use the Find Font command to fix the problem, but ignore it for now by pressing the OK button.

Once the document is opened, if you don’t have the Amatic Bold font installed, the text will appear highlighted in pink to alert you that the missing font has been substituted with one that you do have on your computer. You could also consider it a none too subtle reminder that you need to fix this – which you will shortly.

Before you fix the font problem you’ll address the missing link. Click once on the Links Panel to open it, and notice the red question mark icon in the link status column next to the visit_cuba_white.eps file.

Double click on the question mark icon to relink the file*, which is another way of saying that you’ll tell InDesign where it can locate the missing image.

* If you have InDesign CS6 or later you might have noticed there is also a missing link icon on the logo itself. You can alternatively relink by double-clicking directly on that.

To finish the process of relinking you now have to locate the original image. In this case I’m going to tell you where it is, but in everyday work you’d possibly need to search on your computer, ask a colleague, client, photographer or designer to send it to you. Look in the Logos folder (inside the Preparing InDesign documents for print folder) and click on the visit_cuba_white.eps logo to relink it. When you return to the document you’ll notice the red icon has disappeared.

Whilst in the Links Panel click on the visit-cuba-vinales-a3.jpg image and look at its resolution in the Link Info Panel. Notice that the Effective ppi of this image is 72. This means that it’s a low resolution image, suitable for viewing on screen, but not for being commercially printed.

For the purposes of these exercises it doesn’t make any difference what the image’s resolution is, but on a real project it’s important that the images are of sufficient quality. As mentioned previously they should ideally be around 300ppi. If they are not, you’ll be taking a risk that they will look poor quality. If this happens to you, your options are to source higher resolution images from the photographer, use different images, use them at smaller sizes, or as a last resort resample the image using Photoshop’s Image Size command (which is beyond the remit of this post).

Notice also in the Link Info that this image’s Colour Space is RGB and not CMYK. Whilst this is something that can’t be adjusted in InDesign, the program makes it easy for you to open the image in Photoshop and change it there. Before you learn how to do this I should mention that whilst it’s commonplace for designers to use Photoshop to convert images from RGB to CMYK, it’s not strictly essential to do this, because if you create a pdf from InDesign using a setting such as [PDF/X-1a:2001] it will convert any RGB images and swatches to CMYK as it does it.

To open the image in Photoshop make sure the image is selected at the top of the Links Panel, press on the dropdown menu at the top right of the panel and choose Edit With from the list of commands that appear. A list of suitable programs will appear – if you have Photoshop installed on your computer, choose that.

In Photoshop, choose Image>Mode>CMYK. Then save and close the file, and return to InDesign. When you click on the image the Info Panel should now indicate that it is a CMYK image.

About missing fonts

In the same way that InDesign needs access to the original images that have been placed in a document before creating a pdf, it also needs access to any fonts that were used when creating it. As you’ve already seen, you will be altered by means of a dialogue box and the pink highlighting of text that you need to deal with missing fonts. To have a closer look at this, from the Type menu choose Find Font.

The Find Font command lists all of the fonts used in the document and highlights ones that are missing by means of a yellow exclamation mark icon. In this document only one font is used, Amatic Bold, and it is missing.

How you’ll handle missing fonts will be depend on the circumstances. In some cases the font that is missing might not be critical for the design or branding and can be easily substituted for another one you do have. In that case you’d use the Find First and Change or Change All buttons on the right to search for the places where the font is used have InDesign replace it with a different one. But it’s more likely that you’d fix the problem by installing that font on your computer. The font used here is one whose designer has made freely available. If you want to install it, press the Done button to leave the Find Font dialogue box*.

* If you’d rather not install it, follow these instructions to replace it with a different font that you have on your computer. Click on the Amatic Bold font at the top of the dialogue box, choose a font from the list at the bottom of the dialogue box, then press the Change All button to replace every instance of Amatic Bold with the font of your choice.

You can download the Amatic Bold font for free from

www.fontsquirrel.com. While you’re there you might also want to download the Permanent Marker, Signika and Ubuntu fonts that you’ll use in later exercises. Instructions on how to install them can be found at www.fontsquirrel.com/helpYou might find this Wiki How tutorial useful for installing on a PC: www.wikihow.com/Install-Fonts-on-Your-PC and Mac users can find a similar tutorial here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=3AIR7_ch9No

Once you’ve installed the font and returned to InDesign you should notice the pink highlight has disappeared, indicating that the font is no longer missing.

About Bleeds

As you know, the black border around every page edge indicates the edge of the document, but that’s not the full story. When you send an InDesign document to a commercial printer they are often printed on sheets or rolls of paper that are larger than the document size. They are then trimmed down to size on a guillotine, whose blade is lined up with Trim Marks (see the diagram below).

The black border represents where the trimming should occur. However, as the guillotine blade runs through a stack of paper its blade may bend slightly, and your document may be trimmed slightly inside or outside the black line. To account for this, any elements that need to appear right at the edge of a page need to continue, or ‘bleed’ over the edge. A bleed guide makes it straightforward to create bleeds, as objects snap to the guide that sits just outside the edge of the page. The diagram below shows a close up of the top left corner of a document with a bleed guide.

As you can see from the screenshot below, this poster has a photograph that extends to the edge of the page on every side, and so it should have a bleed guide. However there is no bleed guide, and the image simply stops at the edge of the page. If the bleed guide wasn’t set up when the document was created it can be added later. You’ll do this now by choosing Document Setup from the File menu.

At the bottom of the Document Setup dialogue box you should see a dropdown button next to the words Bleed and Slug*.

* If you’re using a version of InDesign prior to CC (any of the CS versions) you’ll instead press the More Options button towards the top right of the New Document dialogue box to reveal the Bleed and Slug values.

Once you can see the Bleed and Slug values, enter 3mm for one of the Bleed values and click on the padlock to apply the same value to all edges of the document. Then press the OK button.

You’ll now see a red bleed guide has appeared just outside the edge of the document.

Choose the Selection Tool from the Tools Panel and click on the edge of the frame that contains the picture.

Using the Selection Tool, drag the square handle on the top left of the frame out to the bleed guide. Do the same thing with the handle on the bottom right of the page, creating a 3mm bleed.

Finally, you’ll create a pdf. Use File>Export as you did previously and choose the [PDF/X-1a:2001] preset from the options at the top of the Export Adobe PDF dialogue box. The pdf you created previously was for an advert, and the assumption there was that the advert would be placed somewhere in the middle of a page in a magazine, alongside others. Because of that it would not be printed on its own, nor need to be trimmed down to size, nor need to allow for any bleed. This poster is different. As it’s going to be printed conventionally it is advisable to add printers marks – things like trim marks they can use to trim the document once it’s been printed. To do this, firstly click on Marks and Bleeds from the list on the left hand side of the dialogue box.

In the Marks and Bleeds section of the PDF Export Dialogue box, check both the All Printer’s Marks checkbox and the Use Document Bleed Settings checkbox before pressing the Export button.

If you look at the finished pdf (by double clicking on it, outside of InDesign) you’ll see the trim marks around the edge of the document, and also the area of the image outside the bleed guides that should be trimmed off once the document has been printed.

Summary of what you’ve learned in this section

Prepare Illustrator File For Screen Printing

How to relink a missing image

How to change an RGB image to CMYK

How to recognise a low resolution image

How to notice / replace a missing font

How to add a bleed guide

How to export a pdf with bleeds and trim marks

Prepare Illustrator File For Wcreent Printers

Summary of new commands used

Prepare Illustrator File For Wcreent Printable

Links Panel>Relink (or double-click on missing link icon)

Links Panel>Edit With

Type>Find Font

File>Document Setup

If you’ve been working through these exercises to try and understand what to do in order to send your own documents to print, at this point you’ve already covered everything that’s generally likely to arise. If you want to gain an understanding of some other issues that are less likely to arise (such as spot colours and transparency issues) and an insight into some useful InDesign features like Packages and Preflight, please sign up below to download our free pdf (email address required).

This is an adapted version of a chapter from our InDesign CC Creative Classroom book.

Comments are closed.